Once gold was discovered and the California Gold Rush began, more than 500 camps, villages and towns sprang up almost overnight as some 80,000 prospectors poured into the Mother Lode country in 1849 alone. For more than a decade, the flood of people continued to come,arriving overland on the California Trail, by ship around Cape Horn, or through the Panama shortcut. In the beginning, the miners easily gathered the surface gold, scratching more than $10 million from the land in 1849. By 1853 the yield had peaked at more than $81 million before dropping in 1855 to $55 million.

Among these tens of thousands of prospectors and an almost equal amount of claims, tales of "lost mines" began almost immediately as pioneers were killed, sickened, or lost their way back to many of the rich ore finds in the mountains and deserts of the Golden State. Whether these tales of lost mines are fact or fiction, their legends are still alive for hopeful prospectors of California.

Cement Gold Mine of Mammoth Mountain

In 1857 two German men who had been traveling with a California-bound wagon train, left the rest of the group and headed out on their own. Winding up in the Mono Lake region of northern California, one of the men would later describe the area as "the burnt country." While crossing the Sierra Nevada near the headwaters of the Owens River, they sat down to rest near a stream. Here, they noticed a curious looking rock ledge of red lava filled with what appeared to be pure lumps of gold "cemented" together, hence, the name.

The ledge was so loaded with the ore that one of the men didn't believe it to be real, laughing at the other as he pounded away about ten pounds of the ore to take with him. The believer drew a map to the location and the two continued their journey. Along the way, the disbeliever died and the gold-laden traveler tossed the majority of the samples. After crossing the mountains, he followed the San Joaquin River to the mining camp of Millerton, California. During his journey, the German had become ill and soon went to San Francisco for treatment. He was diagnosed and cared for by a Dr. Randall who told the man he was terminally ill with consumption (tuberculosis). With no money to pay the doctor and too ill to return to the treasure, he paid his caretaker with the ore, the map he had drawn, and provided him with a detailed description.

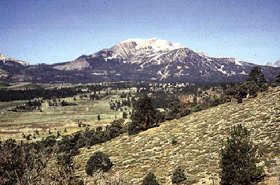

Mammoth Mountain, courtesy U.S. Geological Survey | Dr. Randall shared this knowledge with a few of his friends and together they arrived at old Monoville in the spring of 1861. Engaging additional men to help, Randall's group began to prospect on a quarter-section of land called Pumice Flat. Thought to have been some eight miles north of Mammoth Canyon, the 120 acres were near what became known as Whiteman's Camp. Word spread quickly and before long miners flooded the area hunting for the gold laden red "cement." One story tells that two of Dr. Randall's party had in fact found the "Cement Mine," taking several thousand dollars from the ledge. Unfortunately, for those two men, the area was rife with the Owens Valley Indian War which began in 1861.

|

The Paiute Indians, who had heretofore been generally peaceful, balked at the large numbers of prospectors who had invaded their lands. The two miners who had allegedly found the lost ledge were killed by the Indians before they were able to tell of its location. Though the "cement" outcropping was never found, the many prospectors who flooded the eastern Sierra region did find gold, resulting in the mining camps of Dogtown, Mammoth City, Lundy Canyon, Bodie, and many others. The lost lode is said to lie somewhere in the dense woods near the Sierra Mountain headwaters of the San Joaquin River's middle fork.

|

In 1894, Tom Scofield, a railroad worker, was surveying near the Clipper Mountains northwest of Essex, California when he decided to do a little exploring. When he was about three miles up the side of the mountain, he ran across an old abandoned stone house that appeared to have been built years previously. Continuing along, he hiked approximately nine more miles when he came upon a spring. There, he followed a trail that led over the hill where he came upon a rock atop the peak that he described as being as big as a house. The large boulder was split in two and the trail continued straight through it. Beyond the passageway he stumbled into what appeared to be an old Spanish camp.

| The Clipper Mountains are northwest of Essex, California |

Tom found himself standing on a high shelf, surrounded by high walls. Through other openings in the rock walls, he could see that the "shelf” was sitting high above the ground at about 500 feet. The only way in or out of the little flat was through the split rock. Scattered about the long deserted camp, Scofield found rusty mining tools, pots, pans, fragments of a bedroll, and an old iron Dutch oven. Also on the shelf was a mine shaft, in which he found the skeletons of seven burrows. Next to the shaft was a mine dump that contained numerous stones still containing rich gold quartz. By the time he had finished exploring the campsite, he realized that it was too late to return to his base camp. Cold and hungry, he bedded down on the shelf planning to leave at daybreak. In the morning, as he was leaving, he tripped over the Dutch oven and out tumbled a mound of pure gold nuggets. Shocked, Tom gathered as many nuggets as he could carry and returned to his base camp. From there he caught a train to Los Angeles, where he spent the next two months in a drunken frenzy, gambling and living the high life. After squandering all the money he had received from the sale of the gold nuggets, Scofield found himself sober and completely broke. It would be two years before he was able to make his way back to the Clipper Mountains to search for the "Dutch Oven Mine.” Try as he might, it seemed to him that everything had changed and he was completely unable to retrace his steps. Disillusioned, he finally gave up the search. When Scofield was 84, he was interviewed by Walter H. Miller and George Haight in 1936. Living in an abandoned store in the Mojave Desert outside Danby, California, Scofield was at first hesitant to tell his story. After having been hounded for four decades by treasure hunters wanting more information about the mine, he had long tired of the story even though he continued to insist that it was true. Today, the Dutch Oven Mine continues to be lost, or at least no one has ever claimed to have found it.The Clipper Mountains are located in the Mojave Desert of southeastern California. The range is found just south of Interstate 40 and the Clipper Valley, between the freeway and National Old Trails Highway, northwest of the small community of Essex. The range is home to at least three springs, as well as the Tom Reed Mine.

|

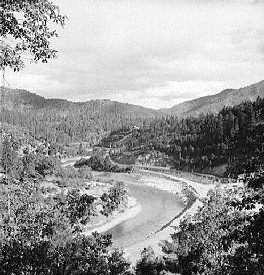

Goose Egg Mine of El Dorado County - As early as 1848, gold was found in the Mosquito Valley of El Dorado County, California. As more and more people found their way to the Gold Rush country, hundreds of mining camps sprung up all over the region. One that flourished was Newtown, some nine miles southeast of Placerville.

Established in 1852, Newtown was first settled by Swiss immigrants who spoke Italian and called the village "Sunny Italy.” Growing quickly, Newtown boasted a post office, several retail establishments and about 5,000 residents, with some claiming it was bigger than Placerville. Rich with placer gold, theWells Fargo Express began serving Newton three times a week and passenger stage routes were added later.

|

Using a cradle to find gold in 1883

|

Tales abounded of the easy gold to be found. On one occasion two large nuggets, one weighting 36 ounces and the other 42, were plucked from the South Fork of Webber Creek, one mile down stream from Newtown, in Pleasant Valley. Into this midst of easy findings and quick fortunes came a young immigrant from Finland who went by the name of "Sailor Jack.” Though the naïve man knew absolutely nothing of gold mining, he was determined to make his fortune in the goldfields. No sooner had he come to town when several experienced miners, as a practical joke, convinced the newcomer to file a claim on a piece of land they knew to be worthless. But as fate will have it sometimes, the joke ended up being on the pranksters when Sailor Jack struck pay dirt on his claim and the mine became one of the richest in El Dorado County. Called theSailor Jack Mine, it was also known as the Pinchgut Mine, the One Spot Mine, and the Pinchemtight Mine. In its early days the placer mine, located about 1 ½ miles north of Newtown, yielded about $40,000 worth of gold. It was during these frenzied days of working the Sailor Jack Mine that one of the miners employed there found yet another rich discovery. In a location above the Sailor Jack, in an area called Goose Neck Ravine, the miner found several large gold nuggets. Upon returning, he shared his discovery with several other miners who thought that the nuggets might have come from the lead source of the Sailor Jack. Though the prospector, as well as several others, returned to the area time after time, they could never find the spot where the nuggets were picked up. From that time on, the site has been referred to as the Lost Goose Egg Mine. Today, there is nothing left of Newtown except an old stone building and a cemetery near the intersection of Newtown Road and Fort Jim Road about eight miles southeast of Placerville. The Sailor Jack Mine was located about 1 ½ miles due north of Newtown near today's Webber Reservoir.

Gunsight Mine of Death Valley

This image is available for photographic prints HERE.

| In 1849, a group of California bound emigrants were headed out of Utah with a 107 wagons led by Captain Jefferson Hunt. However, by November, the group disagreed on the most direct route to the gold fields. Some believed there was a much shorter route across the desert, rather than taking the well known route along the Old Spanish Trail. Though Hunt warned them that they were "walking into the jaws of hell,” several members of the group parted near Enterprise, Utah, believing the shortcut would save them about 20 days of travel. They would become known as the "Lost 49’ers,” nearly starve on their journey, discover silver, and give the valley its name.

|

The splinter group consisted of several smaller parties, who would also disagree on the best way to cross the vast desert. Before reaching White Sage Flat, the party split once again, with one group hiking over the Panamint Mountains and the other traveling along the floor of the valley. The two parties met up again at White Sage Flat, where one Jim Martin displayed silver ore that he had found while crossing the mountains. Exhausted, starved, and dehydrated, the group had little interest in mineral riches, focusing only on survival. After four months of travel across the vast desert lands, the tattered emigrants finally stumbled into Mariposa happily crying, "Good-bye, Death Valley." During the terrible journey the pioneers had killed their oxen for meat, burned their wagons, and were forced to walk most of the way on what had become a "shortcut to hell.” In the meantime, the party who had stayed with Captain Hunt’s group had already arrived in California. After settling in Jim Martin, who had lost the sight off his rifle during the journey, took the silver ore to a gunsmith who made it into a new gun sight. The story quickly spread, touching off one of the west’s great prospecting booms and the legend of the Lost Gunsight Mine. One of the travelers, a Mr. Turner, who had been with Martin when he discovered the silver, decided to return to the desert in search of the silver. Failing to find it, he soon came upon a ranch belonging to Dr. E. Darwin French near Fort Tejon. Telling the doctor the tale, French and Turner mounted a second expedition to search for the silver outcropping in September, 1850. They too were unsuccessful.

In the mid 1850’s prospectors were roaming the mountains and creeks of Siskiyou County along the northern boundary of California in search of their fortunes. Gold had been found in Humbug Creek as early as May, 1851 but a group of disillusioned miners dubbed the place as "humbug” when they failed to find any of the precious metal. However, that did not stop other prospectors from looking and a few years later when another group hit pay dirt, hundreds of miners flooded into what would be called the Humbug Mining District. Soon, a mining camp was formed along the banks of Humbug Creek called Humbug City.

|

|

It is near here that the Legend of the Lost Humbug Creek Mine began. When a man who was working for one of the Humbug District mines began to feel ill, he started to Yreka, some ten miles to the southeast to see a doctor. Shortly after coming upon the Deadwood Trail, he began to feel so ill that he lay down beneath a tree. As he looked around, spied a promising piece of quartz float and exploring further he found an entire outcropping. Suddenly felling better, he traveled some three or four miles back to his cabin, returning with a pick and shovel. He soon took out a sack full of gold that was estimated to have been worth $5,000 to $7,000. Excited to share the news, he soon traveled to Hawkinsville, where his parents and two brothers lived. Afterwards he returned to the site for more gold, when he began to feel sick once again. Leaving his pick and shovel, and covering the site with brush, he went to the county hospital where he died a week later. Search as they might, his family was never able to find the site of their dead brother’s gold. The outcropping is said to be on the west side of the Humbug Mountains. Long before the white settlers rushed into El Dorado County duringCalifornia's Gold Rush days, natives of the Hawaiian Islands had arrived here in the early 1800’s. These islanders, known as Kanakas, first worked the ships engaged in the hide and tallow trade before forming permanent settlements at a number of places in the Golden State. In El Dorado County, they lived in Kenao Village, named for their chief, and farmed the surrounding land.

The Hawaiians were one of first settlers to establish a town in El Dorado County, farming the land and living quietly before gold was discovered. However, when gold was discovered, they too joined the many miners flooding the area, as well as selling their produce to miners in Coloma. Before long, the miners began to call the village, Kanaka Town.

One of the Islanders by the name of "Kanaka Jack” soon appeared in the village, working a mine along Irish Creek, not far from town. Known to have brought large amounts of gold out of what became known as the Kanaka Jack Mine, he never told anyone of its exact location. In 1912, the Hawaiian miner died at the county hospital.

Today treasure hunters continue to search for the lost Kanaka Mine in El Dorado County.

Striking it rich. This image available for photographic prints and

| In the 1850’s several men from "back east” had come to the Golden State in search of their fortunes. While prospecting in Shasta County in northern California, they crossed the Sacramento River at Cow Creek about 2 ½ miles east of Fort Reading. From there, the prospectors followed another creek eastward for about thirty miles when they came upon a high waterfall. There, they found a rich gold deposit sitting above the waterfall. However, this was a dangerous time in the region as Indians, fed up with miners encroaching upon their lands, were often known to attack.

|

Taking from the gold deposit what they could carry, the soon fled in fear of the natives. Returning to the Fort Reading, they asked for protection, but no troops could be spared. Soon, the men returned east from whence they came. Years later, in the 1870’s, one of the men from this original group, along with his son-in-law, returned to the area in hopes of once again locating the waterfall. In Redding, he asked around about a creek with a high waterfall and was told there was one on Bear Creek near Inwood, some 25 miles to the southeast. The pair soon arrived in Inwood, telling their tale of the Lost Water Fall Mine and spending weeks exploring Bear Creek Canyon. However, after a long search, the two finally gave up and headed back east, never to be seen again. Locals speculated that the country surrounding Inwood in primarily made up of volcanic rock and thought it an unlikely site for gold to have been found. More likely, many believed that the gold might have been found on another waterfall on Clover Creek about three miles from Oak Run and 25 miles east of Redding.

|

Hope you enjoyed the stories if so please visit my American Made Prospectors store and also join my blog today thanks , mike | T |

|

|

|

|

|

|